Knee Biomechanics

Normal Knee

The medial femoral condyle (MFC) is larger and located more distally compared to lateral femoral condyle. Like wise, The medial tibial plateau is lower and has a more concave shape, to accomodate MFC jutting more distally. This provide stability and support. In contrast, the lateral tibial plateau is positioned higher and has a convex shape. This over all anatomical arrangement contributes to the complex biomechanics and movement patterns of the knee joint.

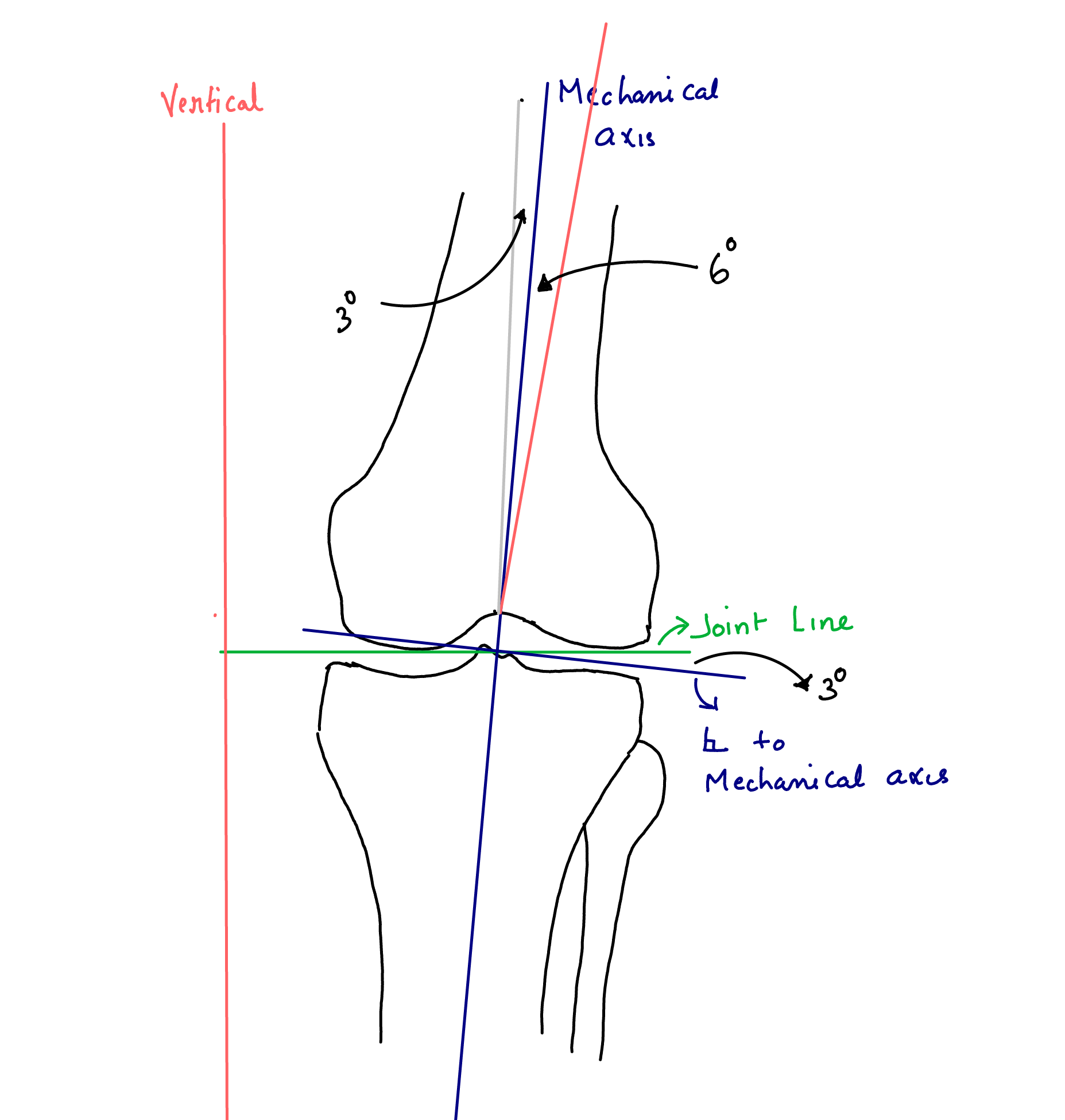

The joint line (green) is perpendicular to the vertical line drawn from the centre of pubic symphysis (red).The Mechanical axis (purple) extending from the centre of the hip-joint to the centre of the ankle is at 3° varus to the vertical Figure 1.

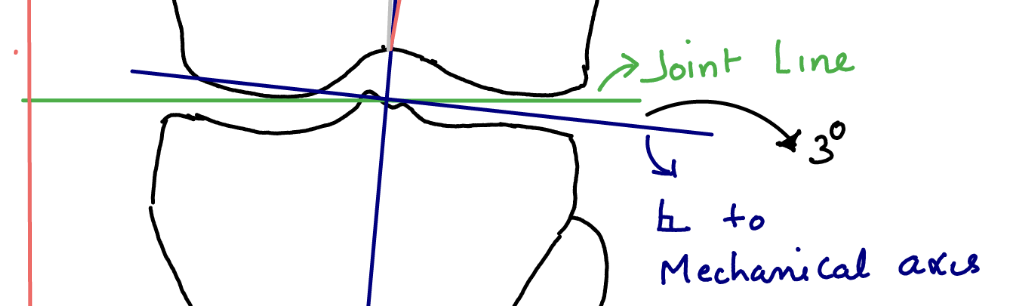

Coronal alignment refers to the mechanical axis of the lower limb, which typically passes just medial to the lateral tibial spine.Due to the 3° varus angulation of the distal femur, which is parallel to the joint line, it is positioned at a 3° valgus relative to the mechanical axis. In a normal knee, the tibial plateau is angled approximately 3° in varus with respect to the mechanical axis. How ever, during total knee replacement (TKR), cuts are made perpendicular to this axis to ensure even loading of the prosthetic components.

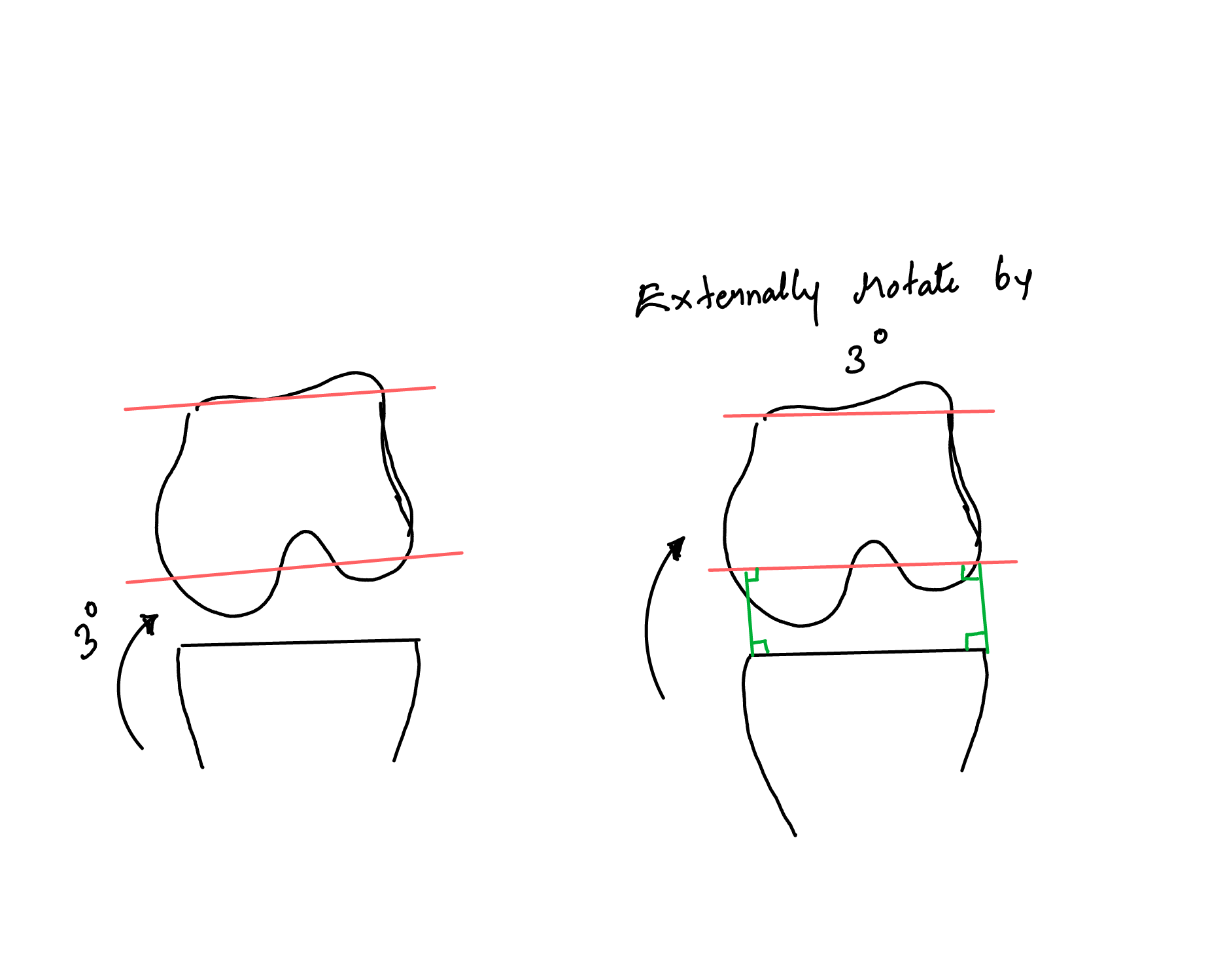

For the posterior and anterior femoral cuts, the posterior condyles are used as a reference point Figure 2. Notably, the posterior condyles are also at a 3° varus angle to the mechanical axis. Therefore, when performing TKR, the cutting jig should be externally rotated by 3° to achieve a cut that is perpendicular to the mechanical axis. Figure 3. Similarly, the proximal tibia, which is again parallel to the joint line, is positioned at a 3° varus angle to the mechanical axis.1

In terms of sagittal alignment, the mechanical axis of the knee is located just anterior to the midpoint of the tibial plateau. This alignment is stabilized by the posterior capsule and surrounding ligaments. Regarding tibial slope, a 7-degree posterior slope is considered normal, with the lateral tibial plateau having a slightly greater slope than the medial side, allowing for balanced joint movement.

During normal Knee motion, Flexion-extension axis corresponds to transepicondylar line

Femoral rollback

Femur rolls and slides posteriorly during flexion to increase the lever arm of quadriceps enhancing their functional capability and also to allow for deeper knee flexion.

However, femoral rollback is not symmetric due to the differing articular geometries of the medial and lateral compartments. In the medial compartment, the large medial femoral condyle (MFC) conforms to the convex medial plateau, while the medial meniscus is relatively fixed with only 0.5 cm of excursion, resulting in fairly uniform flexion. Conversely, in the lateral compartment, the lateral plateau is concave, and the lateral meniscus is mobile, allowing for an 11 cm excursion. This mobility permits the femoral condyle to slide and rollback on the lateral plateau. The differential rollback creates a polycentric instant center of rotation during flexion, resulting in a J-shaped curve when plotted, as it moves posteriorly with flexion. Additionally, the lateral femoral condyle (LFC) externally rotates during flexion, which corresponds to relative tibial internal rotation, and internally rotates during extension, corresponding to relative tibial external rotation. The knee achieves a “screw-home” mechanism and locks the knee in full extension, which is the most conforming and stable position for the joint. In this extended position, the cruciate ligaments are taut, further enhancing joint stability. Energy expended by the muscles to keep knee in this position is zero.

The popliteus muscle originates from the posteromedial border of the tibia and extends to the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle (LFC). Its primary function is to unlock the knee from the extended position. Upon contraction, the popliteus facilitates femoral external rotation and tibial internal rotation, allowing for the transition from full extension to flexion.

Popliteus flexus and LaFtER

Patellofemoral joint

The patellofemoral joint plays a crucial role in knee function, with the patella acting as a pulley that enhances the quadriceps lever arm. This biomechanical advantage is significant, as evidenced by studies showing that patellectomy can lead to a 20% decrease in quadriceps power.

The Q angle, formed by a line from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the center of the patella and a line from the center of the patella to the tibial tuberosity, typically ranges from 5 to 20 degrees, with women often exhibiting a larger Q angle. An increased Q angle can result from any condition that result in lateralization of the ASIS or tibial tuberosity, leading to a lateral pull on the patella during extension and contributing to flexion instability. This can cause uneven distribution of patellofemoral contact pressures, which may contribute to the development of patellar arthrosis. Factors such as an increased Q angle, a shallow trochlea (dysplastic), or a deficient medial patella facet (Wiberg type 3) can exacerbate this issue. In normal patellofemoral motion, the patella engages the trochlea at about 20 degrees of flexion, conforming well to the groove during deep flexion; however, it is most prone to instability in extension. The patella’s contact pressures are significant, with the thickest cartilage in the body measuring approximately 1 cm. During flexion, the contact pressure is about 0.5 times body weight, while activities such as going upstairs and downstairs increase this pressure to 2.5 times and 3.3 times body weight, respectively.

Restraints to abnormal knee motion

Anterior tibial translation

| Type of Restraint | Structures | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Static Restraint | - Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) | Main restraint against anterior tibial translation. |

| - Anteromedial bundle (tight in flexion) | ||

| - Posterolateral bundle (taut in extension) | ||

| Secondary Static Restraints | - Collateral ligaments | Provide additional stabilization. |

| - Iliotibial band (ITB) | Contributes to knee stability. | |

| Dynamic Restraint | - Hamstrings | Control knee movement and provide dynamic stability. Rehabilitation is essential post-ACL injury to enhance knee stability and prevent excessive anterior translation. |

Posterior tibial translation

| Type of Restraint | Structures | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Static Restraint | - Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) | Main restraint against posterior tibial translation. |

| - Anterolateral bundle (tight in flexion) | ||

| - Posteromedial bundle (taut in extension) | ||

| Secondary Static Restraints | - Posterolateral corner | Contributes to knee stability. |

| - Lateral collateral ligament | Provides additional stabilization. | |

| Dynamic Restraint | - Quadriceps | Control knee movement and provide dynamic stability. Strengthening is essential for maintaining proper knee function and stability, especially after injuries affecting posterior tibial translation. |

Varus, valgus stability

| Type of Stress | Type of Restraint | Structures | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Varus Stress | Primary Static Restraint | - Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) | Provides support against inward bending of the knee. |

| Secondary Static Restraints | - Posterolateral corner | Contributes to overall knee stability during varus loading. | |

| - Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) | Assists in maintaining knee stability. | ||

| - Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) | Aids in overall knee stability. | ||

| Valgus Stress | Primary Static Restraint | - Superficial medial collateral ligament (MCL) | Provides 57% resistance in extension; 75% in 25° flexion. |

| Secondary Static Restraints | - Posteromedial corner | Contributes to valgus stability. | |

| - Deep MCL (attaches to the meniscus) | Acts as a secondary restraint in extension. | ||

| Other Stabilizing Structures | - Posterolateral corner | Prevents rotatory instability and posterior translation of the tibia. |

The posterolateral corner of the knee

It plays a crucial role in preventing rotatory instability and posterior translation of the tibia. This region consists of three distinct anatomical layers that contribute to its function.

| Layer | Structures | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Superficial | - Biceps femoris | Provides support and stability during movement. |

| - Iliotibial band (ITB) | Aids in maintaining knee alignment and stability. | |

| - Common peroneal nerve | Lies between superficial and middle layers; important for nerve function. | |

| Middle | - Patellofemoral ligament | Stabilizes the knee joint and assists with patellar motion. |

| - Quadriceps retinaculum | Supports the knee by reinforcing the extensor mechanism. | |

| Deep | - Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) | Provides stability against varus and rotational forces. |

| - Fabellofibular ligament | Aids in maintaining lateral stability. | |

| - Posterolateral capsule | Contributes to joint stability and integrity. | |

| - Arcuate ligament | Stabilizes against posterior and lateral forces. | |

| - Popliteus muscle | Unlocks the knee from extension and provides rotational stability. | |

| - Lateral geniculate artery | Supplies blood to structures in the posterolateral corner. |

Knee Arthroplasty Biomechanics

Constraint vs. Contact Stresses

- The balance between constraint and contact stresses is crucial in determining loosening versus wear in total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Conformity

- Conformity refers to the degree of anatomical match between the femur and tibia. High conformity minimizes point loading, which in turn reduces wear.

Full Constraint

- A fully constrained knee design provides the highest level of conformity, allowing movement in only one plane. This results in low wear due to high conformity and low point loading; however, it can lead to greater stress at the implant-bone or implant-cement interface, increasing the risk of loosening.

Fully Unconstrained

- Conversely, a completely unconstrained and unconforming design allows for excessive motion and high degrees of flexion but leads to edge loading and wear. Loosening is typically not a significant issue with these designs.

Goals of TKR

Clinical Goals

- The primary clinical goals of TKR include reducing pain, increasing function, maintaining range of motion (ROM), and avoiding complications.

Biomechanical Goals

1. Restoration of the mechanical axis

2. Preservation of the joint line level

3. Creation of equal flexion and extension gaps

4. Well-balanced ligaments

5. Durable component fixation

Design Variables in TKR

Degree of Component Conformity

- There is a trade-off between wear, ROM, and loosening.

Fixation Method

- Options include metal-backed trays or all-polyethylene components.

Femoral Radius of Curvature

- Variations include large anterior, small posterior, or single curvature.

Polyethylene Properties

- Factors include type, shape, thickness, manufacturing, and storage.

Level of Constraint

- Options include PCL-retaining, PCL-sacrificing, and semi/fully constrained designs.

Polyethylene Thickness

- Aim for a minimum thickness of 8 mm, with 10 mm preferred to ensure durability. Thickness below 8 mm increases wear characteristics.

Femoral and Tibial Cuts

The tibia is cut perpendicular to the mechanical axis to prevent uneven loading of bearing surfaces, even though the normal tibia is in 3 degrees varus. If femoral anterior-posterior (AP) cuts were anatomic, this would create an uneven flexion gap. Therefore, AP femoral cuts are made with 3 degrees greater external rotation than the epicondylar axis, ensuring that the femoral component is parallel to the tibial cut in flexion, which creates a rectangular flexion gap.

The distal femoral cut (valgus cut angle) reflects the difference between the anatomical and mechanical axes of the femur, making the cut parallel to the joint line to create a rectangular extension gap. The normal setting is 5-7 degrees valgus; care must be taken with very short or very tall individuals or those with previous trauma or known dysplasia.

Judging Femoral Rotation

Proper femoral rotation is critical for creating a rectangular flexion gap and affects patellar tracking. The epicondylar axis is typically present, even in revision situations. The Whitesides line, extending from the deepest part of the femoral sulcus to the deepest part of the trochlea, should be perpendicular to the femoral axis of rotation. The posterior condyles should be parallel to the rotation axis; caution is advised if the posterior condyles, particularly the lateral condyle, are worn, as this can cause internal rotation.

To ensure accuracy, the tibial cut should be made first, as the tibial cut must be correct to reference rotation accurately.

Ligament Balancing

Varus Deformity - Releases should be performed on the concave side from the tibia:

1. Osteophytes

2. Deep medial collateral ligament (MCL)

3. Posteromedial corner and semimembranosus

4. Superficial MCL

5. PCL

Valgus Deformity - Releases should be performed on the femur:

1. Osteophytes

2. Lateral capsule

3. Iliotibial band (ITB) (if the knee is tight in extension)

4. Popliteus (if the knee is tight in flexion)

5. Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

6. Lateral head of the gastrocnemius

Fixed Flexion - Addressing fixed flexion involves:

1. Osteophytes

2. Increasing the distal femoral cut

3. PCL recession

4. Posterior capsule (pie crusting)

5. Complete release of the PCL

Importance of PCL

The PCL’s primary function is to prevent flexion instability and excessive posterior translation of the tibia while permitting physiological femoral rollback. It prevents impingement of the femur on the tibia, allowing for high flexion. Additionally, the PCL serves as a secondary restraint in varus and valgus stability. PCL-retaining designs maintain femoral rollback and normal kinematics, offering significant advantages.

Patellofemoral Joint in TKR

The patellofemoral joint is particularly important in cases of inflammatory arthritis, as the disease can affect the PCL, leading to greater instability due to the soft tissue component.

Types of Implants: - Dome: Eliminates problems with rotational alignment; the most common design. - Anatomic: Provides better conformity but has a lower margin for error in positioning. - Mobile Bearing: Metal-backed, providing another interface for wear while reducing polyethylene thickness.

Tracking Issues

Any alteration in the Q angle can lead to maltracking and impingement pain. Malrotation of components, including internal rotation of the femur or tibial component, can cause relative external rotation when the knee is reduced. This can be minimized by laterally positioning the patella button and lateralizing the femoral component.

Patella Baja

Patella baja occurs due to elevation of the joint line or excessive distal femoral resection, resulting in shortening of the patellar tendon. This can lead to impingement of the patella’s distal pole on the polyethylene in flexion.

Failure in TKR – Technical Reasons

Poly Thickness: - If the polyethylene is too thin (<8 mm), contact pressures may exceed the yield strength, leading to early wear.

Poorly Conforming Design: - Results in increased contact pressures and greater wear.

Backside Wear of Poly: - Occurs between the polyethylene and the base plate; more prevalent in all TKRs, though reduced by using an all-polyethylene tibia.

Manufacturing Issues: - Previously a cause of catastrophic failure.

Loosening: - Increased stress on the bone-cement or cement-implant interface, often seen in highly constrained designs.

Instability: - Can result from poor balancing or malrotation of components, leading to patellofemoral maltracking.

Patellofemoral Overstuffing: - Can occur from oversizing or undercutting the femur.

Poor Fixation Technique: - Issues such as inadequate cement interdigitation or concerns with uncemented tibia.

Infection: - Risks are heightened by excessive surgical time, poor technique, and soft tissue damage.

Principles of Mobile Bearing TKR

Mobile bearing designs, including meniscal or rotating platform types, are intended to allow component conformity while reducing stress at the implant-bone interface, thereby minimizing loosening. These designs have not yet been conclusively shown to outperform fixed bearing designs, with the main complication being polyethylene spin-out or dislocation.

Footnotes

During total knee replacement, this anatomy plays an important role in deciding the angle of distal femoral cut. We use intra-medullary alignment jig for distal femoral cut. This is at 6° varus to the mechanical axis. Hence we have to take a valgus cut angle of 6° to get an artificial joint line perpendicular to mechanical axis. For toller patients it s less than 6 and for the very short it is more. Tibial cut is taken using an extra medullary alignment jig which is perpendicular to mechanical axis.↩︎